I asked Glynn McCalman, Clyde Vernon McCalman’s brother, to write a paragraph or so describing Clyde as he was before he entered the U. S. Army, and Glynn was kind enough to provide the following:

“Clyde Vernon McCalman was born June 13, 1923, to Odell and Gertrude McCalman at their farm home on the old Shreveport Road south of Walnut Hill. He and his brothers, Marvin, Byrd and Glynn, attended school at Bradley, where Clyde excelled academically and socially.

Clyde continued to excel as a student at Ouachita College during the early years of World War II. He was exempted from service in the war because of his status as an ordained minister, but he was uncomfortable with that exemption. After the death of a close cousin, neighbor and friend, Harland Bird, in a bombing raid over Germany, he felt compelled to offer himself in the conflict.

He volunteered for service in the Army on March 17, 1944, and was killed on the same day one year later, March 17, 1945, in the final weeks of the war in Europe. The letter (in the previous post) was written in the month preceding the month of his death.”

Thanks to Glynn McCalman for providing the above information. For any reader of this site who may not already be aware of it, Glynn is a Bradley area historian and the author of two books on local history: Bradley Connections and Walnut Hill And Somewhere Else.

– – – – –

Clyde’s letter touches on several aspects of an infantryman’s life during active combat, such as the simple pleasure of sleeping inside a building. Perhaps it may be useful to add a clarifying comment to some passages from the letter.

There is a reference in the first paragraph to someone named Hogue. I have no idea who this was, other than someone who was obviously a mutual acquaintance of Clyde and my father.

The third paragraph of the letter refers to the “big German counterattack” and the awful winter weather. This is a reference to what we now call the Battle of the Bulge, which began shortly before Christmas in 1944. It was Hitler’s last serious attempt to break out of the encirclement into which the Allied advances had forced him.

The fourth paragraph of the letter states that “It was my division which cut off the Cherbourg Penninsula and took 1/4 of all prisoners taken on Cherbourg.” This refers to combat operations shortly after D-Day, June 6, 1944, when the Allies landed on the beaches of Normandy in France. Cherbourg, with its fine port facilities which the Allies coveted and which the Germans were determined to defend long enough to destroy, was taken on June 30, 1944.

Clyde states in the letter that he has “five months of combat behind me,” so it is doubtful that he was personally engaged in active combat during the Cherbourg operations. Indeed, that would have occurred only a little more than three months after his enlistment in the U. S. Army. It does, however, provide an idea of how long his unit had been actively engaged with the Germans. Another indication of constant attack operations by the U. S. Army can be found in the comment in the next-to-last paragraph that “We have not been farther back than our own artillery since early October.”

It is ironic that Clyde’s letter states that he had “a comparitively soft job – mil clerk and administrative assistant to the 1st Sgt,” yet he was killed in action a little more than one month later. This is perhaps an indication of the ferocity of the fighting, the urgency to maintain the attack, and the need for every soldier, including the ones with a “comparatively soft job,” to actively participate in the fighting.

– – – – –

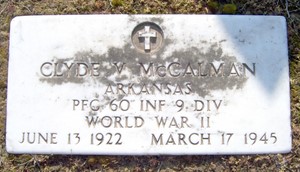

Pfc. Clyde Vernon McCalman’s remains were temporarily interred at Henri-Chapelle in Belgium and were later moved to the Walnut Hill Cemetery. Below is an image of the foot marker on his grave: